Haplotype independence contributes to evolvability in the long-term absence of sex in a mite

Haplotype independence contributes to evolvability: functionally different chromosome sets in a parthenogenetic animal showcase a survival strategy spanning millions of years. Where did we find this? In asexual oribatid mites!

My colleague Hüsna established an HMW gDNA extraction method: now, we can generate phased assemblies using HiFi long- & TELL-Seq linked reads stemming from a single individual and scaffold them into chromosomes with Hi-C data; allowing us to dive deep into asexual genome evolution!

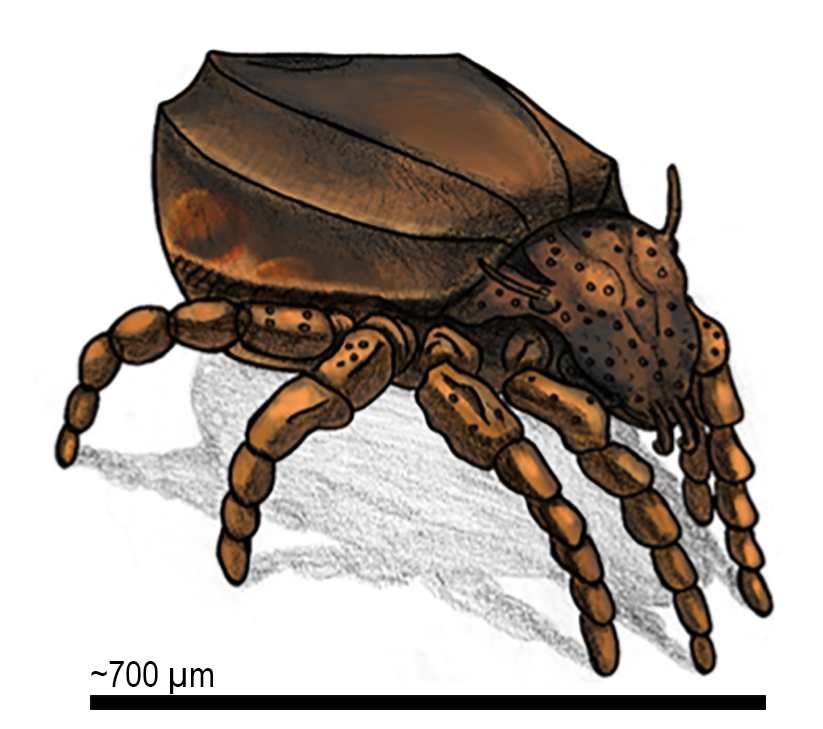

To investigate haplotypic independence we sequenced 5 ind. of the asexual oribatid mite species Platynothus peltifer from 🇩🇪🇮🇹🇷🇺🇯🇵&🇨🇦. As expected under ancient asexuality: the 2 haplotypes display mirror topologies of populations, including all ind. of European populations, representing the ‘Meselson effect’.

Haplotype trees of 🇯🇵 & 🇨🇦 populations lack such clear separation. While some individuals display a shared separation of haplotypes, this is confined to each respective population → suggesting a more recent transition to asexuality.

Asexual oribatid mites are known to maintain effective purifying selection. How they evolve & adapt in the long-term absence of sex remains unknown. We show you lines of evidence that haplotypic independence provides the substrate for evolvability & evolutionary innovation.

Thus far, the Meselson effect & ancient asexuality in parthenogenetic animals only exist in oribatid mites; suggesting that the rarity of long-term asexuals is a requirement for haplotypic independence as a source for novelty to adapt and diversify in the absence of sex.

About my latest work on oribatid mites (featured by BBC, Le Monde, Die Welt, etc.):

It was thought that the survival of animal species over a geologically long period of time without sexual reproduction would be very unlikely, if not impossible. However, an international research team of zoologists and evolutionary biologists at the Universities of Cologne and Göttingen, as well as Universities in Lausanne (Switzerland) and Montpelier (France), has now demonstrated for the first time that animals can reproduce successfully without sex in the long term, perhaps for millions of years. They studied the Meselson effect – a characteristic trace in the genome of an organism suggesting reproduction has been asexual – in the ancient asexual beetle mite species Oppiella nova. The results were published in PNAS.

So far, scientists have observed the great evolutionary advantages of sexual reproduction from the genetic diversity produced in offspring from the encounters of two different genomes that a pair of parents can supply. In organisms with two sets of chromosomes, i.e. two copies of the genome in each of their cells, such as humans and also beetle mite species that reproduce sexually, sex ensures a constant ‘mixing’ of the two copies. That way, genetic diversity between different individuals is ensured, but the two copies of the genome within the same individual remain on average very similar.

However, it is also possible for asexually reproducing species, which produce genetic clones of themselves, to introduce genetic variance into their genomes and thus adapt to their environment during evolution. In contrast to species that reproduce sexually, the lack of sexual reproduction and thus ‘mixing’ in asexual species causes the two genome copies to independently accumulate ‘mutations’ (changes in genetic information), and become increasingly different within one individual: the two copies evolve independently of one another. The Meselson effect describes the detection of these differences in the chromosome sets of purely asexual species. “That may sound simple. But in practice, the Meselson effect has never been conclusively demonstrated in animals – until now,” explained Professor Tanja Schwander from the Department of Ecology and Evolution of the University of Lausanne.

The existence of ancient asexual animal species like Oppiella nova are difficult for evolutionary biologists to explain because asexual reproduction seems to be very disadvantageous in the long-run. Why else would almost all animal species reproduce purely sexually? Animal species such as Oppiella nova, which consist exclusively of females, are therefore also known as ‘ancient asexual scandals’. Proving that the ancient asexual scandals really do reproduce exclusively asexually, as hypothesized (and that they have been doing so for a very long time), is a very complex undertaking. According to first author of the study Dr Alexander Brandt former PhD student at the University of Göttingen and now at the University of Lausanne, “There could be, for example, some kind of ‘cryptic’ sexual exchange that is not known or not yet known”’. Purely asexual reproduction, however, leaves behind a particularly characteristic trace in the genome: the Meselson effect.

For their study, the researchers collected different populations of Oppiella nova and the closely related, but sexually reproducing species Oppiella subpectinata in Germany and sequenced and analysed their genetic information. “A Sisyphean task,” said Dr Jens Bast, Emmy Noether junior research group leader at the University of Cologne’s Institute of Zoology.

“These mites are only one-fifth of a millimetre in size, live in soil and are difficult to identify,” explains Brandt. Analysing the genome data required computer programmes specifically designed for this purpose. Hence, Brandt, Schwander and Bast consulted the experienced mite ecologist Dr Christian Bluhm, former PhD student of the University of Göttingen and now at the Forest Research Institute Baden-Württemberg as well as Patrick Tran Van, a bioinformatician specializing in evolutionary genomics at the University of Lausanne.

Their efforts were ultimately rewarded: they succeeded in proving the Meselson effect. ‘Our results clearly show that Oppiella nova reproduces exclusively asexually. “When it comes to understanding how evolution works without sex, these beetle mites could still provide a surprise or two,” Bast concluded. The results show the survival of a species without sexual reproduction is quite rare, but not impossible. The research team will now try to find out what makes these beetle mites so special.